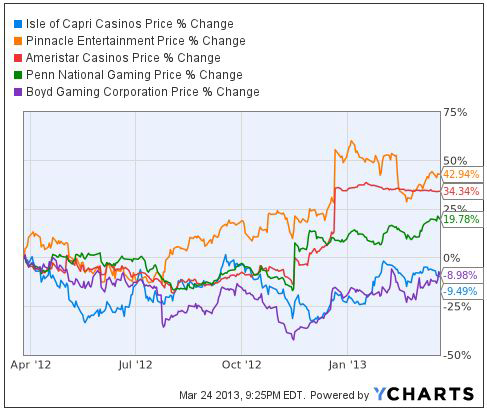

In my tenure here at CalvinAyre.com, I’ve been rather bearish on the stocks of operators of regional casinos here in the U.S. I’ve recommended pairs trades where investors buy Macau operators and sell US ones. I advised selling short the entire US regional sector, and later called Isle of Capri (ISLE) one of the market’s “five dumbest stocks.” I’ve bemoaned the cannibalization facing the sector, as new and/or expanding markets such as Ohio and Maryland steal market share and revenues from neighboring states. And in January, I asked, “Is there any reason to buy US gambling stocks?” and concluded that the answer was no. Yet, despite my pessimism, the share prices of US regionals have held up rather well over the past year:

To be fair, some of these results have been strongly influenced by one-time events. The merger of Pinnacle Entertainment (PNK) and Ameristar Casinos (ASCA) in December caused both stocks to soar roughly twenty percent. The year-long rise in shares of Penn National Gaming (PENN) came solely from the company’s decision in November to spin off a real estate investment trust, limiting its tax liability and (theoretically) boosting its earnings, which boosted the stock 28 percent in a single day.

Without those moves, there would have been only modest gains for the group as a whole, gains that would come in below both those of the broad market and other gambling stocks. And looking at fiscal 2012 results, there should be continued questions about whether such gains can be supported going forward. Revenue figures across the industry showed modest growth – at best. Penn grew revenues 5.7 percent. Revenue fell at Ameristar by 1.6% year-over-year. Boyd’s revenue grew 6.5 percent, mostly due to its acquisitions of Peninsula Gaming and the IP Casino in Biloxi, which combined cost over $1.7 billion. Pinnacle created 5% growth – but over half of that growth came from the opening of its L’Auberge casino in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. And through the first nine months of its fiscal year (which ends in April), Isle of Capri saw top-line improvement of just 1.5 percent. And the sector’s largest player, Caesars Entertainment (CZR), saw year-over-year growth of just 0.2 percent even after excluding the loss of its St. Louis property in a sale to Penn earlier this year.

In essence, regional operators cannot create growth unless they buy it, whether through acquisitions or promotional spending. While Ameristar and Penn held the line, Boyd increased promotional allowances by 7%, Pinnacle by 4%, while Isle’s comps rose 10 percent (again, through the first nine months of fiscal 2013). Three of the five companies now have promotional spending over 20 percent over their gaming revenue, with Pinnacle at 18.6 percent. Penn, in stark contrast, spends just 6 percent of gaming revenue on comps and freeplay.

While the numbers sound bad, management doesn’t sound better. Across the sector, 2012 results were accompanied by caution, and occasionally fear, from regional operating executives. On Pinnacle’s post-earnings conference call, chief marketing officer Virginia Shanks noted that visits had declined across the company’s properties in the fourth quarter, while spend per visit stayed flat. Boyd chief operating officer Paul Chakmak told analysts on his company’s calls that gamblers had “pulled back” in the fourth quarter, a trend that continued into 2013, due to worries about US budget negotiations and the re-institution of the payroll tax on January 1st.

While the numbers sound bad, management doesn’t sound better. Across the sector, 2012 results were accompanied by caution, and occasionally fear, from regional operating executives. On Pinnacle’s post-earnings conference call, chief marketing officer Virginia Shanks noted that visits had declined across the company’s properties in the fourth quarter, while spend per visit stayed flat. Boyd chief operating officer Paul Chakmak told analysts on his company’s calls that gamblers had “pulled back” in the fourth quarter, a trend that continued into 2013, due to worries about US budget negotiations and the re-institution of the payroll tax on January 1st.

But the most detailed and most interesting commentary came from the always-candid and often-blunt management team at Penn, namely CEO Peter Carlino and chief financial officer Bill Clifford.Carlino opened Penn’s earnings call by noting that the fourth quarter was “a little softer than we and you all would have liked,” citing “a despondency” in some customers following the November 2012 presidential election and the aforementioned tax increase. The company lowered its full-year projections for 2013 in the wake of this weakness in late 2012 and early 2013 – primarily in the company’s new facilities in Ohio – and when asked whether Penn thought it could hit the now-lower target, CFO Clifford told analysts the company was relatively confident it would, “unless Congress does something really stupid.”

Management remained typically confident about its plans, and its long-term vision, but took a couple shots at competitors and regulators that highlight an insider’s view of the challenges facing regional operators. COO Timothy Wilmott pointed out that Scioto Downs, owned by MTR Gaming (MNTG), had outspent Penn’s Hollywood property in Columbus “4 to 1” in promotional slot play. Wilmott later explained earnings weakness in the Southern Plains segment (encompassing Kansas, Missouri, Iowa, Louisiana, and Mississippi) as due in large part to “fairly egregious attempts to increase our real estate taxes,” which the company has appealed.

Competition issues were discussed as well, not just in the form of competing casinos and racinos but from internet cafes, of which Wilmott estimated there were over 800 currently operating in Ohio alone. Penn and other casino owners, including Caesars, are lobbying to have the cafes shut down; but in a separate presentation in March, Clifford noted the difficulty in doing so. “A lot of these Internet cafe owners have pretty good contacts with some people in the legislature,” he said at an analyst conference organized by J.P. Morgan. Pointing to Florida, Clifford claimed he had been told that several cafes there were actually “owned directly” by members of the Florida state legislature, an accusation that would seem to be buttressed by recent news that the state’s lieutenant governor was stepping down due to her association with a phony non-profit operator. In yet another presentation, this one at a conference organized by Deutsche Bank, Penn investor relations head Hayes Croushore pointed to the influence of the cafes in Ohio by telling listeners that new customers to casinos in Ohio were getting loyalty cards and then asking how to put a balance on it, believing that they were debit cards similar to those used in the sweepstakes cafes.

Most notably, Penn executives showed significant skepticism toward two of these trends most commonly pointed to as potential growth drivers for US casino operators: high-end expansion and Internet gaming. When an analyst asked if the trends that drove Penn’s reduced guidance might mean the projections for massive potential projects in Massachusetts and Maryland might currently be exaggerated, Carlino seemed to agree. Penn is competing with MGM Resorts International (MGM) in both markets after the two companies spent over $90 million lobbying a Maryland initiative, and Carlino seemed happy to take a shot at two possibly aimed at his counterpart, MGM CEO Jim Murren. “I mean, clearly, there is an irrational exuberance around some of what we’re hearing from our competitors,” he told analyst Ray Cheeseman. “You’ve heard me say on these calls in the past, we don’t like bidding situations because there’s always somebody more stupid out there willing to do something nonsensical.” Toward the end of a long answer, Carlino pointed out that the “days of the giant capital spend, with rare exceptions, are pretty much gone,” and said Penn would only “be competitive up to the point of suicide, then we’ll let the other person commit suicide.” (At this point, it seems likely that Carlino would show little grief if it were Murren who wound up pulling the trigger.)

In the JP Morgan presentation, Clifford showed similar skepticism toward iGaming, claiming his company was in no rush to find a partner or set up its online gambling strategy. Clifford echoed a lot of the concerns I voiced just last month; echoing his boss’ opinion of new high-end resorts, he thought “people were a little exuberant here” in terms of iGaming profits. Clifford argued that iGaming profits would take a lot longer than many thought, and questioned the distribution of those profits, given the limited difficulty in designing and launching a site. Interestingly, Clifford made the argument that Internet-based businesses as a whole simply did not provide high-margin returns, pausing to exclude the porn industry, before admitting that “even they’re not that good anymore.” Unless states focus on giving an advantage to existing operators – as New Jersey’s law appears to – the profits from iGaming may be lost to marketing and promotional costs amid competitive pressures, Clifford said.

In calls, Penn executives give an honest assessment of their environment, and then claim the company’s long-term vision and focus on reacting to economic trends, rather than trying to influence them, will allow Penn to succeed. Given the company’s consistent earnings and share price growth since Carlino took over nineteen years ago, it’s hard to disagree with them. Yet the other companies in the sector lack some of Penn’s advantages, such as a low debt load and the pending REIT conversion. Isle and Boyd are both debt-heavy, while Pinnacle and Ameristar will be dealing with merger integration challenges for the next two years. Penn remains the best-in-breed regional operator, but it also remains priced as such; even assuming the REIT spin-off had already happened, lowering the company’s tax profile, it is trading at 20 times the company’s projected 2013 profits. That is roughly the same multiple as Las Vegas Sands (LVS), which offers exposure to much higher potential growth in Asia.

As for Caesars, its land-based operations are most likely worthless, overwhelmed by the company’s $20 billion debt load. The stock has soared of late, with most of its equity value coming from its interactive division, which has roared higher based on hopes for iGaming profits in Nevada and New Jersey. But the state of its land-based operations was highlighted by Clifford, whose company bought the former Harrah’s St. Louis from Caesars in May. Asked about the St. Louis property, Clifford noted that Penn had higher expenses than expected in taking over the property due to its condition. “The place was filthy,” Clifford said at the JP Morgan conference. “It was disrepair. It was just – elevators didn’t work.”

This is what happens when you have high debt and no revenue growth. You can either try to buy growth and grow your way out; but that is a high-risk strategy. You can try to cut expenses; but then you’re not marketing enough in a competitive environment and you wind up with casinos whose elevators don’t work. You can try to increase promotional spending and free-play; but that lowers margins, meaning the added revenue growth does little to boost the bottom line. These are the options available to most of the US regionals right now, and none of them look particularly attractive. And, to be honest, neither do many of their stocks.