In my columns here at CalvinAyre.com I’ve been noticeably skeptical about the potential for online gambling, particularly online poker. In April, I largely dismissed Zynga’s online poker aspirations, a case I made again just last month. In September, I noted that the coming move to mobile gambling was far more likely to boost profits for iGaming operators going forward than the flat, even declining online poker market. In fact, my very first column for this site questioned the rise in gambling stocks after the US Department of Justice issued a revised interpretation of the 1961 Wire Act.

I haven’t necessarily been alone in my skepticism; even in the immediate wake of the DOJ announcement, our own Calvin Ayre predicted that only one US state would have online gambling by the end of 2012, a prediction that looks more accurate by the day. But in writing for a site focused on the gambling industry, my consistent skepticism toward online poker has, on occasion, made me feel like the proverbial turd in the punch bowl.

Part of my reluctance to embrace the profit potential of online poker has come from the well-known challenges facing the industry, such as onerous taxation and unfriendly regulatory regimes. But my main concerns about the long-term viability of online poker come from my own experience as an online player here in the US. In some six years as an online poker player, I saw the industry change rapidly, with those changes exposing some key fundamental flaws that I believe online poker operators must accept before they can again create a vibrant, growing market.

I started playing online in late 2004, playing freeroll tournaments on the now-defunct Noble Poker. By the summer of 2005, I was multi-tabling cash games on Ultimate Bet. Online poker in 2005 was, without exaggeration, free money. There were players on the Omaha tables who didn’t understand the rules of the game (including the most important one, that two and only two hole cards must play). Hold’em players who learned the game from ESPN made huge bluffs with missed hands but had no understanding how to get value off their winners. I saw players misread boards and bet four-card straights, call off hundreds of dollars with a weak pair of aces, and chase any potential draw for nearly any amount of money. I had notes on a handful of players who bet the exact same fraction of the pot depending on their hand: one-quarter for a flush draw, one-half for top pair, and a full pot bet with three of a kind. For even halfway decent players, the money was flowing; for operators, the getting was just as good. PartyGaming would go public in the summer of 2005, with its initial public offering creating three newly minted billionaires and, as The Guardian noted at the time, valuing the company at nearly $9 billion USD, above British icons such as Rolls-Royce and British Airways. It seemed too good to be true.

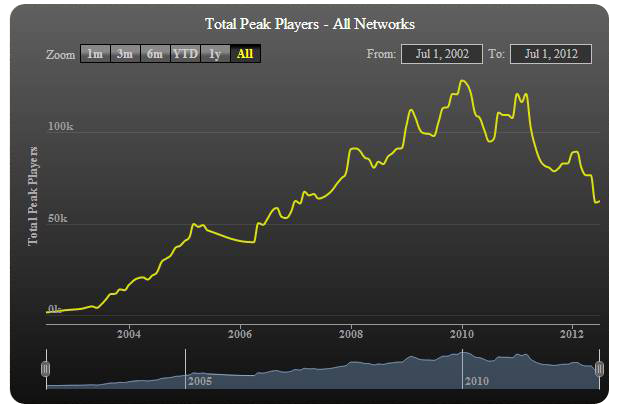

And, in a way, it was. In my memory, those first six months or so of ring games were the peak of online poker; the games would get progressively tougher over the next six years. Many industry observers blamed the 2006 passage of the Unlawful Internet Gaming Enforcement Act (UIGEA) for bursting the poker bubble. I believe its impact was overstated. Certainly, the UIGEA may have harmed the game’s reputation a bit in the States, and players with small accounts on sites like PartyPoker – which closed to US players – may have cashed out rather than moving to UB or PokerStars. But US poker revenue in 2011 appears to have been roughly equivalent to 2005 levels, showing that the industry did recover after UIGEA’s passage. Indeed, data from PokerHistory.eu shows that worldwide liquidity continued to climb after the bill passed in September 2006:

Again, this is a chart of worldwide peak usage, not just US players, but given the US’ importance to the worldwide online poker market, it’s clear that the UIGEA did not have the impact its supporters might have hoped. After all, PokerStars became the dominant player in the market after UIGEA, precisely because it was so easily able to attract US customers with Party’s departure. And, until Black Friday in April 2011, it was not difficult at all to get funds from the US onto Stars or Full Tilt – or to get them back. (That obviously changed after Black Friday, most notably for Full Tilt customers.)

What changed for players was not the law or the funding mechanisms, but the games themselves. They became significantly more difficult. Interestingly, what happened in online poker mirrored the many booms and busts of Wall Street over the past few decades. Each time the financial industry devised a new product – whether “junk bonds” in the 1980’s or derivatives in the 2000’s – the initial profits were enormous. There was little or no competition. As others saw the money flowing in, they entered the market, driving profit margins down, forcing existing players to increase their leverage, and eventually wiping out any chance for all but a few to make significant money. The same thing happened in poker. In 2005, there simply weren’t very many good poker players. Fewer still had much experience playing No Limit Hold ‘Em or Omaha; as the World Series of Poker itself has noted, limit hold ’em was “the king of all games in the 1990’s,” with Seven-Card Stud dominant in the Northeast.

But over the next few years, players improved, applications such as PokerTracker and Hold’em Manager became widespread, and suddenly there were a lot more sharks at the tables. Win rates declined, forcing hard-core players to increase their multi-tabling and/or the length of their sessions. The term “grinder” came into use, with many players sitting at 8 or 12 tables at a time for multi-hour sessions, eking out small profits based in part or wholly on rakeback and bonuses. By 2008, the games were completely and totally different. It was rare to find cash game players playing a single table at a time; even most losing players were clearly well-versed in poker odds and theory. Many players – myself included – looked to tournaments, particularly sit’n’go’s, as a way to regain the edge seen at the height of the “Moneymaker boom.” But a proliferation of books, software programs, and training sites turned single-table tournaments into essentially a solved mathematical problem, with ICM (Independent Chip Model) calculations forming nearly the entire decision-making process. By the end of 2010, I’d nearly quit; the profits were too small, and the volatility too great. When the Black Friday indictments were announced, I cashed out a few hundred dollars from PokerStars when it became available, and moved on to live games here in Oklahoma. (Full Tilt still owes me about eight dollars.)

It’s impossible to overstate just how dramatic the change was in online poker between 2005 and 2011. The game moved completely from a recreational, somewhat even playing field to being dominated almost solely by professionals. To be fair, operators are aware that the game has changed, and have attempted to address those problems. iPoker has split its network in two, attempting to fence off weaker players from multi-table grinders. Bodog has created a controversial “Recreational Poker Model” that mandates anonymous tables, defeating the player tracker tools used by sharks. The purpose of these moves is to protect the “net depositors” – ie, losing players – from the winners long enough to make the games worth their while. As Bodog’s Jonas Odman wrote on this site, the model “will mean that net depositing players get more entertainment for their money which will increase player retention.”

These efforts to protect recreational players have taken some criticism, but they are absolutely essential to maintain liquidity and create growth in online poker, because the biggest challenge facing net depositors is the inherent nature of the game. Online poker’s Achilles heel is also one of its most attractive features: its speed. The speed of the game, in and of itself, does not allow any except the luckiest of weaker players to put together any sort of successful streak of sessions. A live player might see 35 or 40 hands per hour; an online player will see at least double that, and if he or she is multi-tabling, might play four or five live sessions’ worth of poker in a single afternoon.

And that’s the catch. A live cash game player need only get lucky once – hitting a flush draw, flopping a full house – to have a decent chance of coming out ahead for the day. A live tournament player needs one hot streak to propel him to the final table. Either way, a regular, losing poker player can still have winning streaks that last for a couple of weeks. Online, those streaks might, at best, translate into a single winning session, or a strong early run in a large tournament before the player’s luck runs out. In short, the speed of online poker, and the number of hands played, simply overwhelm a weaker player’s ability to get lucky. In addition, live players often don’t track their outlays nearly as well as the online sites do – where one click can show a player’s deposit and withdrawal history. In short, live losing players can be fooled into thinking they could be a winning player – or even fooled into thinking they are a winning player.

Overall, the odds that a weak, recreational poker player looking simply to gamble for a few hours can survive a session of 500 or 700 hands are infinitesimal, particularly online, where the skill level is far higher than at live play at corresponding stakes. And if online players feel that they can’t, or won’t win, they won’t play, because there’s nothing else to entertain them. There are no free drinks from good-looking waitresses; no goofy poker stories; no connection to the other players, creating rooting interests for the nice older woman or against the cocky college kid with sunglasses and his hat on backward. Live play, with rare exceptions, is usually fun; it truly is a social game, an experience that is not and cannot be replicated online. There are losing players who enjoy playing live to catch up with friends, or ogle the waitstaff, or simply have some company on a boring weekend afternoon. Many know they’re losers, in the long run, but poker is a hobby. And, on occasion, they win, and sometimes, win big.

And that, to me, is the catch with online poker. Growth in the game depends on growth of net depositors, but there is no way to structure the game to create content, but long-term losing customers. The speed of the game combined with their negative expected value means that all but a few sessions are going to be losers. And gamblers want at least the hope of a winning day. While I’m a net winner at poker, I’m a net loser at other forms of gambling; for instance, blackjack and roulette. But I still play those games. Why? Because sometimes I win. Sometimes, as happened when I was covering a conference in Vegas earlier this year, my best friend and I turn $10 into $875 in two spins of the roulette wheel, and we hug the poor British guy sitting at our table and order massages and $80 steaks and spend the next ten months telling the story to anyone who will listen. Most of the time I lose, but I’ve still had a few drinks and a few laughs and met a few nice people.

No matter what online poker operators do, they cannot extend those experiences to their losing customers. And the expected value of a losing poker player is likely lower than even roulette, hardly a great mathematical choice for gamblers. (If you’re wondering why I play, I’m usually tagging along.) Imagine playing 100-150 spins of roulette an hour. You are simply not going to leave the table with money very often. Now imagine if the odds were worse. That is the mathematical truth of what most net depositors face. Operators must try to help them, by banning or limiting multi-tabling, defeating tracking programs, and creating other means – whether through modified rakes or live-play standards such as “high hand” bonuses and “bad beat jackpots” – to protect recreational players. Because the way online poker is currently structured, the fish get eaten before they even learn to swim. The grinders who are criticizing efforts to support recreational players are missing the key point: the recreational player is headed for extinction. And without those players, the pro and semi-pro grinders will see their games get even tougher, eventually reaching a point where highly experienced online players with a variety of tracking programs are essentially passing chips back and forth, making long-term profits either impossible or not worth the inherent volatility of the game. That’s where online poker has been headed for seven years now, and without the efforts of operators like Bodog, the entire business model will be doomed. It may seem unfair or unsporting to support weaker players; but, from my vantage point, the online poker business will depend on precisely those efforts.