New York’s Attorney General has filed for preliminary injunctions to prevent daily fantasy sports operators from doing business in the state.

New York’s Attorney General has filed for preliminary injunctions to prevent daily fantasy sports operators from doing business in the state.

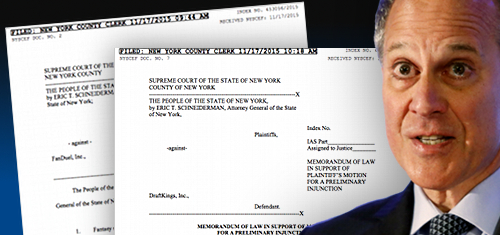

On Tuesday, AG Eric Schneiderman made good on Monday’s threat to file a formal complaint against DFS operators DraftKings and FanDuel, which Scheniderman has accused of conducting illegal gambling as defined by New York state law, as well as promoting illegal gambling activity and engaging in deceptive marketing tactics.

Schneiderman’s move comes one day after a New York judge rejected the operators’ applications for temporary restraining orders that would have prevented Schneiderman taking further action on the cease & desist order he issued last week, which gave the operators five business days to stop serving New York customers.

Following Schneiderman’s filings, FanDuel announced it was temporarily suspending real-money play with its New York players. DraftKings issued a statement on Monday saying it planned to continue operating in the state based on (a) its belief that it was operating legally, and (b) its assertion that Schneiderman had promised not to take further steps until a Nov. 25 court hearing. However, Schneiderman’s office more or less immediately refuted DraftKings’ statement and vowed that criminal proceedings were in the pipeline. And here we are…

Following Schneiderman’s filing, DraftKings issued a statement saying it believes “the Attorney General’s view of this issue is based on an incomplete understanding of the facts about how our business operates and a fundamental misinterpretation and misapplication of the law.” Read on and judge for yourself…

THE CASE AGAINST FANDUEL

Schneiderman’s complaint against FanDuel accuse DFS of being “a new business model for online gambling” and “another way to bet on sports.” Schneiderman quotes various FanDuel execs identifying their target market as sports fans who “cannot gamble online legally,” while noting that FanDuel’s users have a “higher preponderance to gambling” than the norm.

The complaint calls a DFS lineup “a parlay bet in which the relevant variables are the athletes” and cites a FanDuel exec describing DFS as “parlay betting on steroids.” Schneiderman notes that FanDuel hired the head of affiliates for online gambling site Full Tilt to help acquire new customers, and FanDuel’s affiliates include sports betting and handicapping sites Vegas Insider and BetVega.

The complaint includes a FanDuel investor presentation slide comparing the site’s performance to online gambling operator Bwin.party digital entertainment, in which FanDuel “dropped the pretense of referring to the bets on the FanDuel site as “fees,” instead comparing FanDuel’s total “stakes” by quarter to the equivalent numbers for Bwin.party’s sports betting operation.

Schneiderman also goes after DFS commercials’ emphasis on the likelihood of the average player winning a cash prize. One FanDuel ad features a testimonial that “even the novice can come in and spend one or two dollars and win $10,000-$20,000.” But Schneiderman claims that 74% of FanDuel’s top 10k players by cumulative amount wagered lost money between 2013 and 2014.

Finally, Schneiderman slams FanDuel for its previous policy of allowing employees to play on other DFS sites. Schneiderman cites FanDuel’s DFS Play Policy, which instructed employees to minimize their public presence “so users are less likely to be suspicious or angry” and to avoid becoming a top-five player by betting volume because “top players frequently become targets for accusations.”

THE CASE AGAINST DRAFTKINGS

Schneiderman’s complaint against DraftKings covers much of the same ground, while noting that DFS wagers “depend on a ‘future contingent event’ wholly outside the control or influence of any bettor,” an activity prohibited under the state constitution. Schneiderman calls the future contingent events restriction “a statutory test that requires no judgment of the relative importance of skill and chance.”

Schneiderman slams DraftKings’ argument that “selecting the lineup determines the winners and losers” as “incomprehensible,” noting that the same logic applied to traditional sports betting would mean that picking one team to win automatically determined the outcome of the wager. DFS bettors can guess as to how players might perform but “no bettor – no matter how shrewd or sophisticated – can control or influence whether those athletes will succeed.” (Emphasis in the original.)

Schneiderman notes that DraftKings’ argument “misses a more obvious point” because there can be no results of DFS contests if the actual sports events are cancelled, for example, by being rained out. “This is what it means for a wager to be contingent on a future event.”

To illustrate DFS players’ lack of control, Schneiderman cites last week’s Chicago Bears game in which QB Jay Cutler took a knee on the final play, costing the team one yard and reducing Cutler’s DFS production by one-tenth of one point. This one action reportedly cost a FanDuel player $20k by relegating his lineup to second place in a DFS contest, while elevating another DFS player to the top spot and gaining him an extra $20k.

The complaint cites an NBA contest on DraftKings in which the margin of victory separating first place from second place was “equivalent to less than one missed jump shot.” As such, Schneiderman suggests “a well-considered lineup picked by an experienced DFS player could easily take home a lesser prize or no prize – while a randomly assigned lineup could win the jackpot.”

New York law prohibits gambling that relies to a “material degree” on the element of chance, “notwithstanding that skill of the contestants may also be a factor.” Schneiderman says chance “plays a significant role’ in DFS results, be it via “player injury, a slump, a rained out game, even a ball taking a bad hop.”

Noting the DFS companies’ own comparisons of their product to poker, Schneiderman points out that while poker may require some skill, “the game is still gambling. So is DFS.”

Schneiderman cites the Lawrence DiCristina poker case as one in which New York courts have determined that a game’s reliance on a certain amount of skill is no defense against illegal gambling charges. Schneiderman cites other cases in which New York courts determined that the ability to handicap horse races or determine the outcome of a shell game doesn’t erase the element of chance necessary for a conviction.

While Schneiderman focuses on dismantling the skill argument, he strikes an opposite stance by claiming that DraftKing’s marketing efforts misrepresent the average DFS players’ likelihood of winning a prize. Schneiderman contrasts DraftKings’ claims of easy winnings with the site’s own stats that show 89.3% of DFS players had a negative return on their investment between 2013 and 2014.

Schneiderman says DFS players are showing up in increasing numbers at Gamblers Anonymous meetings and problem gambling counselors’ offices, meaning the DFS contests “are causing the precise harms that New York’s gambling laws were designed to prevent.”

Schneiderman also goes after DraftKings’ claims of observing the law in other jurisdictions. Schneiderman notes that New York law defines “gambling” and “contest of chance” in the same manner as Washington state, where neither DraftKings nor FanDuel claim to operate.

Yet Schneiderman says his investigators turned up evidence that DraftKings accepted nearly $500k in entry fees in 2014 from player accounts registered in states where DFS play is explicitly illegal, and from which DraftKings claimed it didn’t accept action.