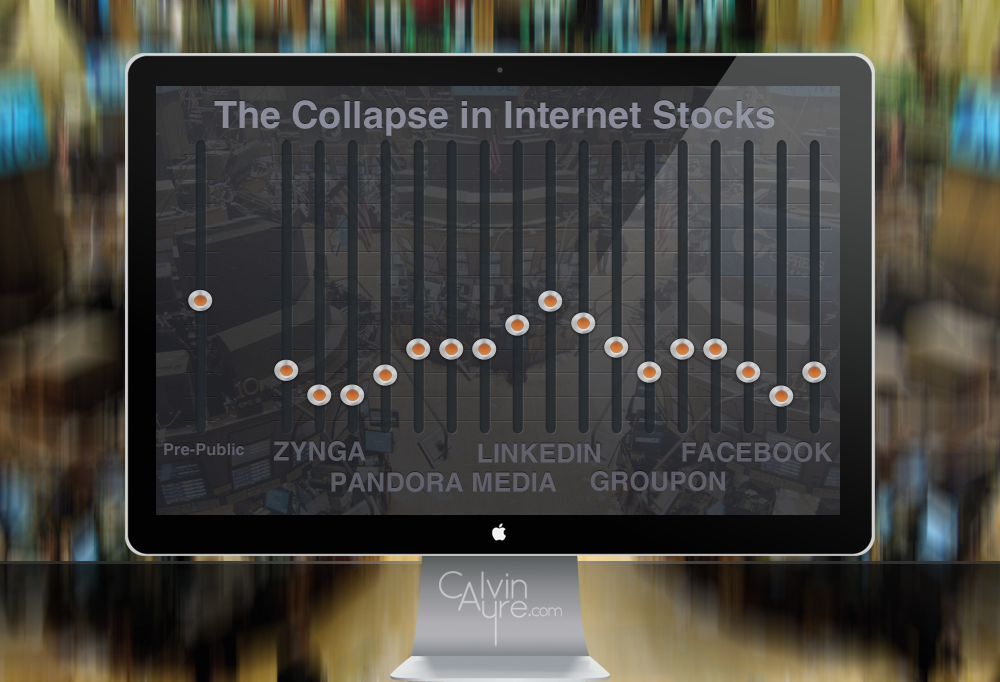

It was heralded as the new dot-com boom. Companies like Zynga (ZNGA), Pandora Media (P), LinkedIn (LNKD), Groupon (GRPN), and, most notably, Facebook (FB), have all gone public in the last fifteen months, using their extensive user bases and strong revenue growth to raise billions of dollars in the public equity markets.

But like the first dot-com boom, the second dot-com boom has largely fizzled. Zynga and Groupon are off more than 70% from their IPO prices in late 2011. Facebook trades lower than half its initial price, while Pandora is off 40 percent in its fifteen months as a publicly traded company. Only LinkedIn – which hit an all-time high of $120.63 on Friday – has survived the carnage.

But like the first dot-com boom, the second dot-com boom has largely fizzled. Zynga and Groupon are off more than 70% from their IPO prices in late 2011. Facebook trades lower than half its initial price, while Pandora is off 40 percent in its fifteen months as a publicly traded company. Only LinkedIn – which hit an all-time high of $120.63 on Friday – has survived the carnage.

The drop in the “new Internet” stocks shouldn’t have been all that surprising; back in May I called Zynga and Groupon two of the dumbest stocks in the market. Two weeks earlier, Forbes had questioned accounting practices at the two companies, while other observers noted potentially fatal flaws in both companies‘ business models.

For investors in the gambling sector, the plunge in Internet stocks has been interesting to watch, though seemingly irrelevant. True, both Zynga and Facebook have made noise about becoming players in iGaming; but Facebook’s activities in the sphere have been limited while I’ve argued that Zynga’s real-money aspirations are more fantasy than reality.

But the lessons of the second dot-com bust are of paramount importance to investors in gambling stocks, particularly in those stocks with potential exposure to the US iGaming market. Despite the slow pace of legalization – only two states have installed regulated iGaming, on a limited basis – analysts are still assigning surprising valuations to potential online gambling initiatives. Barclays analyst Felicia Hendrix gave a potential valuation to the interactive division of Caesars Entertainment (CZR) of $7-24 per share; her high-end estimate was seconded by noted hedge fund manger John Paulson. Even at struggling companies such as Zynga and bwin.Party Digital Entertainment (BPTY.L), the possibility of US iGaming legalization is used to pitch a bull case for the stocks.

In these projections echoes of both the first and second dot-com bubbles can be heard. In 2000, analysts seemed to believe that each dot-com company would become a market leader; nearly every Internet stock was valued as if it would dominate its segment. Projections for Internet adoption were wildly overstated; in 2000, Forrester Research predicted e-commerce spending would be $185 billion in 2004; actual spending was barely one-third of that, and the $185 billion level would not be reached until 2011. As a result, nearly every company in the so-called “dot-com” sector was projected to show sharp revenue growth; the best case became the expected case. The same thing has happened with the new batch of Internet stocks. Analysts didn’t foresee the move to mobile Internet usage, which was especially damning for advertising-based business models such as those utilized by Pandora and Facebook. As such, revenue growth for those companies has lagged user growth, leading to the struggles in their respective stocks. Analysts assumed every Zynga game would be a hit; that assumption was clearly flawed. Meanwhile, the revenue growth shown by the Web 2.0 companies seemed to overshadow the fact that, with the exception of Facebook, none were making any profits, at least not by generally accepted accounting principles.

A similar miscalculation is taking place in valuing the US iGaming market. I argued back in June that US online poker might only be a $3 billion market, while many commentators on this site – and elsewhere – have argued that the legalization process will take far longer than the optimists predict. And yet bulls argue that online poker can save Zynga. MGM Resorts International CEO Jim Murren – whose company only owns 25 percent of a US-facing joint venture – tells his shareholders that legalization can be a game-changer. Caesars’ CEO Gary Loveman complains that it is Congressional gridlock – not his company’s $20 billion debt load – that is hurting profits. Meanwhile, investors in struggling bwin.Party Digital Entertainment (BPTY.L) and 888 Holdings (888.L) – a Caesars partner – are similarly looking to US for a boost in share price.

The problem is, that not every company can be a winner. In a mature market like the US, the Internet is essentially a zero-sum game. Facebook’s gain is Myspace’s loss; Spotify’s market share upon its US arrival is most likely taken from Pandora; and every new daily deal site in the US has the potential to take revenues from Groupon. The same goes for US iGaming. Even if an ideal bill were to pass Congress this fall – a highly unlikely proposition – there is simply no way that online gambling can rescue MGM, Caesars, and Zynga. There simply isn’t enough revenue – and profits – to go around, particularly given the fact that privately held PokerStars, thanks to its recent deal with the DOJ, looks like to be the likely favorite to dominate a regulated US market.

And yet the valuations put on potential revenue streams from US online gambling are surprisingly high. The $24 per share figure for Caesars’ interactive division estimated by both Hendrix and Paulson puts the value of the online operations alone at some $3 billion, more than triple Caesars’ current market capitalization. Given Zynga’s struggles with its legacy social games, its potential real-money gambling operations will need to be worth nearly a billion dollars to justify its already-depressed share price. Meanwhile, MGM’s joint venture would need to be worth at least $4 billion simply for its value to cover the cost of one year’s interest on the company’s $13 billion in debt.

There is a larger point here, too: time and time again, Wall Street and individual investors have massively overstated the potential of the Internet. Groupon and Zynga have collapsed; Facebook has gone nowhere but down in its four months as a public company. Even Netflix (NFLX) – a profitable company with a clear, market-leading niche – is some 80% off its peak last summer, while LinkedIn and Amazon.com (AMZN) trade at astronomical multiples to relatively small earnings.

Perhaps, it will be different for Internet businesses in the gambling sector. But it seems unlikely. The same wild optimism that drove Pets.com to a multi-billion dollar valuation in 1999, and Groupon to a stunning $20 billion market capitalization last year, seems likely to result in iGaming businesses – and their related stocks – becoming overvalued now. As our own Calvin Ayre has repeatedly noted, public companies are at a massive disadvantage in the iGaming world. Their size makes them less nimble – note, in particular, the struggles at newly merged bwin.Party – and their responsibility to shareholders means they are shut out of the most lucrative online markets, most notably in Asia.

Those who cannot learn from history are doomed to repeat it, as George Santayana once famously posited. The history of Internet stocks is littered with disappointments. It may be different in the gambling sector; but investors would be wise to learn their lessons from online stocks in other sectors. The rosy scenarios often sound fantastic; but the reality doesn’t seem to live up to the hype. It was true for the first dot-com boom, and just as true the second time around. It seems unlikely that the third time will be the charm.