If you’ve played much live poker at all, there’s little doubt you’ve been introduced, probably against your will, to the broke-dick gambler. Maybe you’ve run into him actually sitting at a table, playing poker. More likely you’ve encountered him in his natural habitat, hanging out on the rail of the biggest games and tournaments running in the room. One way or another, you know him when you see him scoping out players’ bankrolls as they sit down to play.

If you’ve played much live poker at all, there’s little doubt you’ve been introduced, probably against your will, to the broke-dick gambler. Maybe you’ve run into him actually sitting at a table, playing poker. More likely you’ve encountered him in his natural habitat, hanging out on the rail of the biggest games and tournaments running in the room. One way or another, you know him when you see him scoping out players’ bankrolls as they sit down to play.

Once upon a time, this guy made a big score. Maybe it came in the form of winning a prestigious tournament, usually at least a decade ago when the fields were smaller. More likely it was making a televised final table at some overpriced, poorly attended, fly-by-night tournament series in downtown Vegas that a million people saw on a third-rate cable channel during the early years of the poker boom. There’s even the outside possibility that he was sitting in a middle-limit ring game one night with a bunch of people watching and got hit in the face with the deck when some drunk fish in the mood to set his cash on fire, reinforcing the impression some people have that lucky and good are the same thing in poker.

Whatever his exploits, the broke-dick gambler has never used them to lift himself up into the big games, or to enjoy life’s comforts, or to do most of the things that people dream of doing with a big score. He’s still right where he was before his big score, but that hasn’t stopped him from using it as advertising for himself since the day it occurred. Experienced players know to steer clear, but every now and again he’ll reel in some fish who appears impressed by his tales of yore and agrees to a staking arrangement.

For a broke-dick, the moment of finding someone else to take on the risk of keeping him in the game is when the real business begins. Finding other gamblers willing to buy percentages of his action in return for a share of any profits becomes a priority; this allows him to make a little dough off of having a seat at the table regardless of how the cards treat him. If he’s particularly unscrupulous he might even sell more than 100 percent of his action with the plan of throwing the game and profiting with zero financial risk to himself. More often than not, though, he’ll just leave himself with so little of his own action that anything less than an outright win can never earn really big money for him. Even if fortune smiles on him and adds another score to his resume, the next day just about always will find him right back on the rail, advertising himself for the next stake.

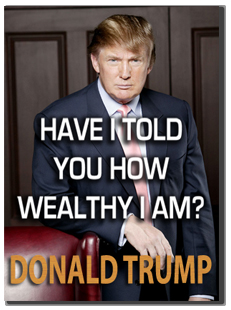

Projecting the image of success

If all you know about Donald Trump is what you’ve seen on television, you might be under the impression that he is one of the most successful men in the world. As TV likes to tell us, this billionaire jet-setter is a self-made man. He owns numerous casinos. His name is attached to lots of really big buildings. He’s written a lot of books. And he was very nearly a candidate for President of the United States this year. If that doesn’t say success, what does?

Behind the curtain, Trump isn’t nearly as great and powerful as he seems. This “self-made man” got much of his money from his father, the New York City real estate developer Fred Trump. He removed himself from the board of the casino company bearing his name, Trump Entertainment Resorts, four days before it filed for Chapter 13 bankruptcy in 2009, marking its third bankruptcy filing in less than 20 years. Many of the buildings that bear his name around the world are actually owned by other investors, with Trump instead serving as a public face for the developers in exchange for a fee or a cut of sales. The topic of all of his books – including page-turners like 1987’s Trump: The Art of the Deal, 1991’s Trump: The Art of Survival, and 1997’s Trump: The Art of the Comeback– is how successful he is. And just weeks after becoming the butt of jokes by sitting US president Barack Obama at the annual White House correspondents’ dinner and drawing widespread national scorn for promoting the “Birther” movement conspiracy theories about Obama’s birth certificate, Trump aborted his fledgling non-campaign for the presidency.

Beyond all of that there are more spectacular failures, including stints as the owner of a football franchise in the United States Football League, which failed to take on the National Football League, and as financial advisor to spendthrift boxer Mike Tyson. And beyond its multiple bankruptcy filings, his casino company also had a case brought against it by the Securities and Exchange Commission over “misleading statements in the company’s third-quarter 1999 earnings release.” (That complaint was settled without anyone having to admit to any guilt or wrongdoing.)

None of this is to say that Trump hasn’t made any money – far from it. In recent years, his wealth has been estimated by outside parties at levels as low as $200 million and as high as nearly $2.7 billion, a small fraction of the money that has flowed through the accounts of Trump and his companies over the years but still a fair sight more than most of us will ever earn. Some of that wealth is thanks to some well-timed past investments in Manhattan real estate, but much of what Trump has caught in his wealth-sieve can be attributed directly to his larger-than-life persona. Not just in a metaphorical sense, either – a company managed by Trump’s children which licenses his name and image to other developers was recently valued by Forbes at $562 million, making it his single most valuable asset.

In essence, Donald Trump’s one true business success is serving as pitchman for a company that sells the idea of Donald Trump as successful businessman. It doesn’t matter whether Trump really is successful in any other venture; he’s mastered the art of projecting an image of never-ending success. In this era of 24-hour celebrity news, that’s pretty much all he needs to do. As long as he keeps himself in front of the cameras – and playing a caricature of himself on a reality show certainly helps with that – he always has a way to generate revenue.

Just keep him away from the controls

Now, with talk of a legalized online gambling industry in the United States beginning to heat up, Donald Trump is looking to get in on the action. This is despite the fact that, like a business version of the broke-dick gambler I told you about before, the three-time casino bankrupter no longer actually has any major ties to the brick-and-mortar gambling business. Those ended when he left Trump Entertainment’s board of directors in February 2009. So who’s the guy who got talking to The Donald on the rail and was drawn by tales of his past glory into a staking agreement? That role is being played by Avenue Capital Group, the hedge fund headed by billionaire Marc Lasry.

Avenue assumed control of the bankrupt Trump Entertainment last year – the same casino company that had Donald Trump as its Chairman of the Board of Directors until four days before it declared bankruptcy to relieve itself of $1.2 billion in debt. When a US Bankruptcy Court judge was deciding who would gain control of Trump Entertainment, Avenue found itself competing against a partnership of two men with actual experience in making profits from businesses that didn’t involve marketing their personas. The first was billionaire investor and former casino magnate Carl Icahn; the second was billionaire banker and occasional nosebleed-stakes poker player Andy Beal. Facing that formidable competition, Avenue cut a deal with Trump to license his name and likeness in connection with the company in exchange for 10 percent stock in the reorganized company. That turned out to be a shrewd move. Trump Entertainment’s bondholders felt that the Trump brand would leave the company stronger than would any sound stewardship from Icahn and Beal. So did the federal judge, who awarded Avenue control of the company.

That leaves us right back where we started with The Donald. Clearly, the lure of the Trump brand is very strong, both to business types and to various departments of the federal US government – strong enough that it’s no stretch to believe that Trump is likely to somehow get himself a stake in any explicitly legalized American online gambling industry. And as long as the money men rely on his ability to pitch himself as a success, they’ll probably do quite well for themselves – he’s an overbearing blowhard with all the charm of the rake, but people apparently go for that in modern America. But should the money men decide to give hand Trump the reins and history begins to repeat itself, they should expect no empathy. Bankrolling the broke-dick on the rail is a lonely business.