In my third quarter review last week, I emphasized a long-running theme of this column: given the low-growth nature of the gambling sector, investors must focus on a company’s ability to execute. And the most important prerequisite for execution is good management.

For investors, judging managers is much like judging potential romantic partners: it takes a while to figure out who the great ones are, but it’s much simpler to figure out who to avoid. If you ignore your intuition, and try to rationalize a reason for staying with someone who is clearly flawed, you are likely going to get hurt – and potentially lose a large amount of money.

The importance of management isn’t just limited to the gambling sector, of course; over the past year, well-known stocks have been crushed by management decisions that were questionable to most observers. Whether it is Research in Motion (RIMM), the maker of the Blackberry, whose co-CEO famously boasted, “There will never be a Blackberry with an MP3 player or a camera,” or the management-led plunge by RadioShack (RSH) into irrelevance and potential bankruptcy, or the “Qwikster” debacle at Netflix (NFLX), there are recent examples throughout the market of the often multi-billion-dollar cost of reckless management and failed execution.

The importance of management isn’t just limited to the gambling sector, of course; over the past year, well-known stocks have been crushed by management decisions that were questionable to most observers. Whether it is Research in Motion (RIMM), the maker of the Blackberry, whose co-CEO famously boasted, “There will never be a Blackberry with an MP3 player or a camera,” or the management-led plunge by RadioShack (RSH) into irrelevance and potential bankruptcy, or the “Qwikster” debacle at Netflix (NFLX), there are recent examples throughout the market of the often multi-billion-dollar cost of reckless management and failed execution.

What these examples show is that once evidence of management’s failure first comes to light, investors need to leave – quickly. When an open letter to BGR was published in June 2011 denouncing former co-CEO’s Jim Balsillie and Mike Lazaridis, RIMM stock had collapsed from $70 to about $28 per share. Too many investors saw the company’s numbers – a single-digit price-to-earnings ratio and strong historic cash flow generation – and rushed in at the new lower levels, while those who were already burned failed to cut their losses. But the stock kept plummeting, Balsillie and Lazaridis resigned, and RIMM is now in the single digits, closing Friday at $8.22 per share. RadioShack’s failed attempt to become a smartphone vendor dropped the stock from $12 to $5 before former CEO Jim Gooch’s delusional justifications for that strategy became public on a post-earnings conference call. It went on to fall another 60%, to barely $2 per share, with Gooch finally resigning last month. Netflix fell sharply after a botched price hike and the later-rescinded decision to re-brand its DVD service; even after all that, it was trading over $150 per share. A little over a year later, Netflix trades at just $66.

Investors must remember that they are giving their money – hundreds or often thousands of dollars – to the CEO to manage. The CEO and his or her team decide how much money to give back through dividends or share repurchases; how to properly invest those funds; and even how much of that cash to pay themselves. A tremendous amount of trust is required; when executives violate the trust, investors should take their money elsewhere.

Back in May, I chose the “Five Dumbest Stocks In The Market.” Among them: Zynga (ZNGA). While I had already noted my skepticism about the company’s real-money gaming prospects, I noted that even if I was wrong on that score, the stock was not a good play. Why? A 2011 total of $510 million in stock-based compensation to employees and an insider sell-off in March proved the company had a “clear emphasis on favoring employees and insiders over shareholders.” Five months later, Zynga stock has fallen by some 70 percent, executives are fleeing with their stock option proceeds in hand, and the company’s bookings are declining.

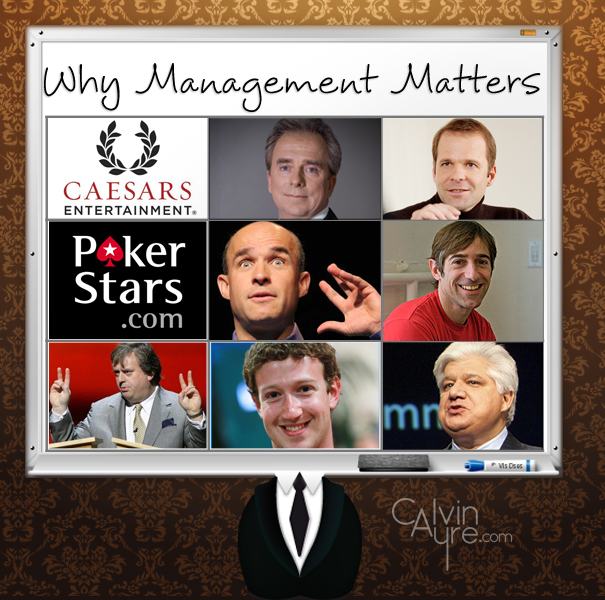

Note that my bearish call on the stock was not based on economic modeling or a microscopic reading of the company’s public filings that unearthed a heretofore unnoticed detail. Zynga’s compensation policies and its secondary offering were widely covered, and widely known; too many investors simply chose to ignore those red flags. Incidentally, number two on the list was Groupon (GRPN), which had twice revised its filing for its initial stock offering after SEC criticisms of its “creative accounting.” It now trades at $5.25 per share, barely half of its $10 level in May. In both cases, the bear thesis was remarkably simple: if you can’t trust the management, you can’t trust the stock. It doesn’t matter how good-looking the girl in the bar is; if she spends two hours talking about how much she loves her ex-boyfriend and how much she hates her father, you should probably move on. In the case of Zynga – which now has about two-thirds of its stock price in cash and still hopes for some type of real-money gambling profits – the stock is starting to get better looking. But the question to ask is simple: would you give your money to CEO Mark Pincus? Between his bias toward himself and his fellow executives, and his wasteful acquisitions, it should be clear to investors that their money is just not safe with the CEO or his company.

Zynga isn’t the only gambling stock with governance issues. bwin.Party Digital Entertainment (BPTY.L) has seen a 20 percent bounce since hitting all-time lows after reporting disappointing first-half earnings in late August. Even including that rise, however, BPTY shareholders have seen losses of some $2 billion in market capitalization since the merger of bwin and PartyGaming was announced in July 2010. As I noted last week – and my fellow contributors here at CalvinAyre.com argued even before the union was completed – the merger itself was based on seriously flawed logic. Indeed, the severe destruction in the stock price, and the market share issues at the combined entity, should have been easy to see coming. The motivation behind the plan was questionable as well; our own Steven Stradbrooke noted that executive compensation would jump sharply in the wake of the merger. “The people at the top of the (bwin.Party) pyramid driving this deal expect to emerge with fists full of cash. We strongly suspect that the average shareholder will be left holding the bag,” he correctly predicted in January 2011.

Despite the failure of the merger, co-CEO’s Jim Ryan and Norbert Teufelberger remain at the helm, while revenues stagnate and PokerStars runs circles around BPTY’s fading poker business. As I noted last month, those investors still waiting patiently for a turnaround need only listen to Oscar from the US version of The Office: “It doesn’t take a genius to know that every organization thrives when it has two leaders…where would Catholicism be without the two popes?”

Another stock to avoid for similar reasons is Caesars Entertainment (CZR). Caesars’ current public status came courtesy of a manipulated IPO in February that CNBC’s Gary Kaminsky called “the dumbest thing I’ve ever seen.” The entire process was clearly orchestrated to allow Caesars’ private shareholders – the same people who bought the company out at the top of the market in 2007 – to exit their positions at a higher, manipulated price. Indeed, CZR jumped from $9 to over $16 on the first day of trading; yet the strategy has failed. The stock has dropped almost without interruption since April; only a 4% gain on Friday to $6.58 boosted it above its low for the year.

The company has discussed the idea of spinning off its interactive business, which includes the World Series of Poker brand and game developer Playtika, shielding those potentially valuable assets from the company’s $20 billion debt load. Indeed, a bull case for the stock at its low current levels could be made, based on the potential value of the spin-off and the possibility that Caesars’ legacy land-based operations can somehow survive its crushing debt load.

But again, we come back to management. CEO Gary Loveman led the 2007 buyout, which he even he now admits was “ill-timed,” according to remarks reported last month by the Review-Journal. The question for new CZR investors is: whose side will Loveman take? The manipulated nature of the IPO makes clear that Loveman’s intent in managing Caesars as a public entity was not to look out for his new shareholders, but to take care of his old ones. The IPO was designed so that institutional investors such as Deutsche Bank, Goldman Sachs, and Paulson & Co. could sell their stakes on the open market at a price higher than they could get on the private market. That effort failed; but it still makes clear where Loveman’s interests lie.

Loveman also is guilty of a very common flaw found in many bad managers: the failure to take responsibility. In the conference call following Caesars’ second quarter earnings release – when the company announced it had posted a $242 million loss – Loveman (20) complained about “a weakening U.S. economy” and the slow pace of online poker legalization. But it wasn’t the economy or Congress who created the $20 billion debt load that is now slowly strangling Caesars; it was the leveraged buyout, led by Loveman, that will likely lead to the restructuring, if not the outright bankruptcy, of one of the world’s largest casino operators.

In all of these examples, there were clear, obvious signs from management that they could not – or would not – be responsible stewards of their shareholders’ investments. Investors in any stock, in any sector, must carefully scrutinize management, and avoid giving their hard-earned money to managers who have not proven their clear intent to take care of their shareholders. There are thousands of stocks on markets worldwide, and thousands of excellent managers leading many of those companies. If you can’t trust your CEO, go find another one.