Thursday was another rough day for global financial markets, and publicly traded online gambling companies weren’t spared. On the bright side, most fared better than their relative indices, which were off between 4.5-5%. Paddy Power was down 0.49p (1.48%), William Hill fell 5.9p (2.66%), Sportingbet lost 2p (3.79%), Betfair slipped 25p (3.91%), Ladbrokes fell 5.5p (4.37%), Playtech dropped 15.25p (4.65%) and 888 Holdings shed 1.5p (4.88%).

And then there was Bwin.party (Pwin), which dropped 8.5p (7.39%) to close at 106.5p. Only Rank Group shed more value in percentage terms, falling 10.3p (8.6%). Pwin’s fall erased most of the modest gains the company had made this week, following a week in which the stock hit a historic low of 98.6p on Aug. 10. No doubt the abrupt postponement of a new online gambling law in the German state of Schleswig-Holstein played a role in Pwin’s stumble. But as much as they would like to play pin the blame-tail on die Deutschen, Pwin shareholders really have no one to blame but themselves. Or, at least, the 99.4% of them that voted to approve the merger of Bwin and PartyGaming.

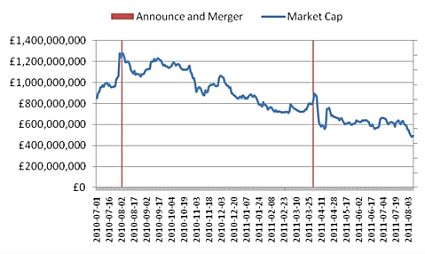

Way back in January, we put the proposed Pwin merger under our microscope, and it was our conclusion that the pairing would not create more value for shareholders – in fact, we found that the opposite was a far more likely scenario. And while nobody likes to say “we told you so”, this graph (pictured right) speaks volumes.

Way back in January, we put the proposed Pwin merger under our microscope, and it was our conclusion that the pairing would not create more value for shareholders – in fact, we found that the opposite was a far more likely scenario. And while nobody likes to say “we told you so”, this graph (pictured right) speaks volumes.

As a standalone company, PartyGaming had a market value of around £1.14b when the intention to merge with Bwin was formally announced in July 2010. By the end of March 2011, when the merger was officially complete, Party’s value had fallen to around £826m. As of August 2011, Party’s 48.4% slice of the Bwin.party pie is hovering below the £500m mark.

Of course, you’d be hard pressed to get the Pwin execs and board members to admit that the merger had failed to create value for shareholders. A KPMG study of the 700 biggest mergers and acquisitions showed that 82% of execs involved in these types of deals were convinced they’d increased shareholder value, despite 83% of these deals having failed to do so. This would be well worth remembering, given the rumors that Pwin was now a takeover target. (Guys, when you’re in a hole, stop merging, er, digging.)

Even before Pwin’s merger was officially announced, the man whose name this site bears predicted that the net result would “not be as powerful in the industry as any of the existing entities are now on a standalone basis.” Calvin also predicted that it was Pwin’s competitors – especially privately held companies – that stood to gain the most from this deal. (Calvin neglected to mention the scheming investment bankers who midwifed this merger mayhem, but that was a given.) And Pwin’s shareholders? Ever wake up with a splitting headache in a grungy motel room to discover both the hooker and your wallet gone? No, us neither.

[An earlier version of this article implied that the chart above represented the market value of both Bwin and PartyGaming, rather than PartyGaming alone. CalvinAyre.com regrets the confusion this may have caused, but it does not alter our conclusion that the merger has devalued both companies.]