Lee and Sue Mullen were a downtrodden English couple that became even more downtrodden in 2005 when their UK Lotto numbers came in, except they’d neglected to play that week because (they claim) they spend their last pound on nappies for their kid. Cue plaintive violins, sober soliloquies on the fickleness of fate, yada yada yada. Fast forward to a couple weeks ago, when Sue has a dream telling her to start buying tickets again. (We’d like to think the dream also said ‘never mind your six screaming brats, let ‘em defecate in the backyard – it never bothered the dog much.’) Despite still being skint, the Mullens picked up a EuroMillions ticket and before you can say EuroMullens, the previously destitute family is £4.8m richer. Suck it, fate!

In Taiwan, a huge lottery prize recently sparked a run on ‘deformed’ pineapples. The fruit’s name in Taiwanese is a homophone for “fortune comes,” and so the local logic goes, a mutant pineapple with multiple heads must be even more fortunate. This sent farmer’s scouring their fields for misshapen pineapples – previously unsellable, they were now fetching 20 times the price of a normal specimen. No one ever accused lottery players of acting rationally.

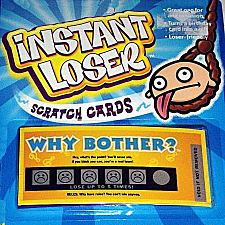

That is, until you meet Mohan Srivastava, a statistician in Toronto. Srivastava caused the Ontario Lottery and Gaming Corporation no end of bother in 2003 when he uncovered a design flaw in OLG’s tic-tac-toe scratch and win tickets. Curious about the algorithm OLG used to control the number of winning tickets, he got out his big brain and started to think. Eventually, the MIT and Stanford graduate realized that he didn’t need to scratch off the latex coating to reveal the ticket’s ‘lucky’ numbers – he could identify winning tickets just by studying the visible numbers on the game squares. After putting his theory to the test, he found that 90% of the time he could identify a winner before choosing which ticket to buy.

That is, until you meet Mohan Srivastava, a statistician in Toronto. Srivastava caused the Ontario Lottery and Gaming Corporation no end of bother in 2003 when he uncovered a design flaw in OLG’s tic-tac-toe scratch and win tickets. Curious about the algorithm OLG used to control the number of winning tickets, he got out his big brain and started to think. Eventually, the MIT and Stanford graduate realized that he didn’t need to scratch off the latex coating to reveal the ticket’s ‘lucky’ numbers – he could identify winning tickets just by studying the visible numbers on the game squares. After putting his theory to the test, he found that 90% of the time he could identify a winner before choosing which ticket to buy.

His joy was short-lived when he realized that even if he decided to cash in on this secret full-time, between traveling to various lottery retailers and the 45 seconds or so it took him to study each ticket, he’d probably only net about $600 per day. Not bad wages for most of us, but it would have been a cut in pay for Srivastava, so instead he took his findings to OLG. Only they didn’t return his calls. So he sent them 20 unscratched tickets and a note saying they were all winners. Within two hours of messengering over the package, OLG called him back. He’d got 19 out of the 20 correct. OLG pulled the cards off the market.

In an interview with ABC News, Srivastava observed that “the lottery corporations all insist that their games are safe because they are vetted by outside companies. They said it couldn’t be broken. But it could.” And it still can. Srivastava recently tried his luck again in Ontario, this time on a bingo-themed scratch card. After one day of study, was able to predict the winners 60% of the time (a one-in-fifty probability). As Srivastava puts it, “there is nothing random about the lottery.”