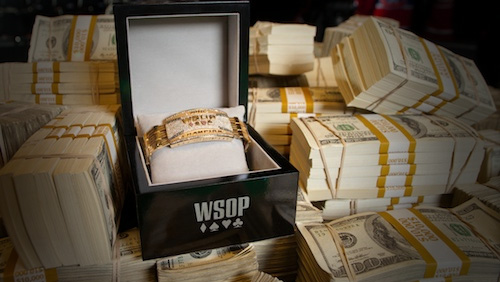

Belgian poker pro Davidi Kitai joined a pretty select club earlier this week when he won Event #15 of the 2014 World Series of Poker, a $3,000 Six-Handed No-Limit Hold’em tournament, for his third WSOP win in the last decade. He became the third player of this summer to win a third career gold bracelet, after Vanessa Selbst and Brock Parker, and just the 65th in the 45 years the WSOP has been running. More interesting was how several of the WSOP’s modern rule changes helped him in closing out the tournament.

The first rule change that worked out in Kitai’s favor was the restriction on the length of days (or “hard stop” rule) first instituted at the WSOP a few years back. Prior to the hard stop rule, the final day of WSOP tournaments would continue running until they played out to a winner. More often than not the tournament would finish before the hour got too late, but every now and then the lack of a time limit meant a final would become just as much of an endurance test as it was a test of poker skill. Two of the best examples are the 2006 $50,000 HORSE event, where Chip Reese beat Andy Bloch after 7 1/2 hours heads-up, and the 2008 WSOP Europe Main Event, where John Juanda finally beat Stanislav Alekhin to end a 22-hour, 434-hand final table.

The first rule change that worked out in Kitai’s favor was the restriction on the length of days (or “hard stop” rule) first instituted at the WSOP a few years back. Prior to the hard stop rule, the final day of WSOP tournaments would continue running until they played out to a winner. More often than not the tournament would finish before the hour got too late, but every now and then the lack of a time limit meant a final would become just as much of an endurance test as it was a test of poker skill. Two of the best examples are the 2006 $50,000 HORSE event, where Chip Reese beat Andy Bloch after 7 1/2 hours heads-up, and the 2008 WSOP Europe Main Event, where John Juanda finally beat Stanislav Alekhin to end a 22-hour, 434-hand final table.

In this year’s Event #15, Las Vegas pro Gordon Vayo entered Day 3 with the chip lead and made it through to the final table, but he was down by nearly 4-to-1 by the time his heads-up match with Kitai began. Over the course of the next 40 hands, Vayo switched up his game and managed to claw his way back into contention, actually taking over the chip lead by a small margin. Then the clock ran up against the hard-stop rule and the tournament staff paused the event for the night. While there was no guarantee he could have stayed ahead had play continued, there’s also no question that the pause took away Vayo’s momentum. Had he been playing in an earlier decade he could’ve pressed his newfound advantage. Instead he went to sleep with a small lead and came back to face a fresh opponent.

Just giving Kitai a chance to sleep overnight and think over what had happened throughout the final table would have been enough to help him, but he had some additional assistance from some other rule changes away from the table. The final table of Event #15, like that of most of the preliminary events during this WSOP, was streamed online on a 30-minute delay, in television-quality video, with hole cards on display. The players have complete freedom of movement, so on breaks they can talk with friends who have been watching the broadcast and learn if there’s anything they should be aware of when they return to the table.

Kitai took advantage of the nuances of the current arrangement for streaming the final table – and, it should be added, did so completely legally – but he got an even bigger break by having the opportunity to go back and watch Vayo’s play. After getting a read on his opponent’s game, Kitai came back on the unscheduled Day 4 and beat Vayo out for the bracelet. “The live stream (on WSOP.com) really helped me make some adjustments,” Kitai told WSOP.com after the tournament. “During the breaks I had some of my friends watching and seeing how (Vayo) played and then I made adjustments. He got really tough heads-up, and after we took the break for the night last night, I was able to watch and see his hand ranges. That was really important to me.”

This is a significant shift from the way things have been in the past. Two years ago all the WSOP live video streams were shown without hole cards, limiting the amount of information that a live-stream viewer could share with a player on break. And way back in 2007, the first year that streaming video coverage of WSOP final tables was offered, hole cards were shown but the players were sequestered with no access to electronic devices or any people who were not also final table participants. Then the stream was still shown on a significant delay as an extra layer of protection against any information leaking to influence the outcome of the game. Official policy was intended to ensure there was no way to have outside sources convey useful information to the players at the final table, things like what kind of big folds or bluffs an opponent was making, or what kind of reliable physical tells he was giving off.

Things are different today. Official policy is more concerned with providing a media product to the masses than maintaining an environment free of outside information, and sometimes that has a significant impact on the outcome of tournaments. Of course, rule changes have regularly affected WSOP events since its earliest days. They were once played as winner-take-all events, players had to put up cash buy-ins for every tournament because there were no satellites, and the entire Main Event field started on a single day instead of in the four flights that make up Day 1 of modern Main Events. And for that matter, the continued delivery of a high-quality mass media product is pretty important for poker at this stage in its development. Providing free streams with hole cards on a delay is good not just for players at a final table but for the overall health of the game. It draws in more casual fans without making them wait months to see big-name poker superstars in action, which will remain a big deal until online poker can return to the U.S. on a large scale.

None of this is said to take away from Davidi Kitai’s accomplishment – he’s a highly skilled player with a track record of excellence and his entry into the three-bracelet club is well-deserved. In fact, as long as the WSOP maintains these rules, Kitai’s success should serve as a blueprint for smart players who find themselves at a WSOP final table. They’ll have someone trustworthy watching the live streams, taking notes to be prepared to talk on short level breaks and, most importantly, the longer dinner breaks. This won’t ever tilt the tables completely in one player’s favor, but when a three-time bracelet winner characterizes anything as “very important” at a final table, you can believe that it’s helping him and is worth looking into – at least until the rules change again and a new strategy has to be devised.