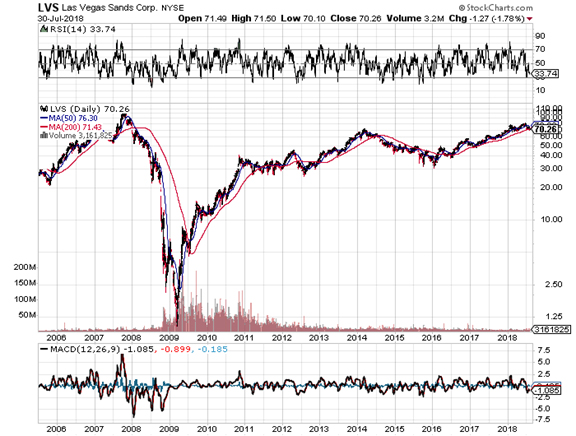

In one of the most spectacular events of overselling in recent history, Las Vegas Sands lost over 99% of its capital value in the 16 months from October 2007 to March 2009. This happened even though the casino was never in any sort of existential, or arguably even any major strategic danger during the last financial crisis. Revenues were even growing, though impairments and doubtful accounts were forcing the casino into losses. But the beauty of balance sheet impairments and doubtful accounts is that they are by their very nature temporary. Obviously business wasn’t exactly booming while the world was in a financial panic, so a decline of, say, 50-70% wouldn’t have been out of the ordinary, but nothing that warranted the stock falling over 99% from its peak.

What causes this is margin calls. When you are forced to sell, you sell at whatever the price is, whenever your broker wants her money back. It’s going to happen again. Margin is not the cause of crashes, but an aggravator of them, because debt pushes prices higher than they would otherwise go, meaning stocks have longer to fall before reaching bottom. How far they go often has nothing to do with company fundamentals. If a big bank crashes, or even several big banks, margin maintenance requirements go up across the board, and forced sales in totally unrelated securities start. A crash in Bank of America or JP Morgan can lead to forced sales in LVS or anything else for that matter. And it doesn’t matter how much margin people are using to trade LVS specifically, at all. If there is a margin balance in a brokerage account, all positions in any stocks in that portfolio are at risk of getting liquidated at any price.

Just to give you an idea of where we are now, consider the FINRA margin statistics. At market top in late 2007, total NYSE margin debt (on which LVS trades) was $379.6 billion, combining both FINRA and NYSE statistics. By February 2009, margin debt had fallen below $200 billion as margin calls forced the liquidation of debt. More importantly though, when margin debt was at its peak in 2007, total credit balances remaining were $426.7 billion, still much higher than the total margin peak. As of June, we are now at $646.9 billion in total NYSE margin debt, with a free credit balance of $179.4 billion, much lower than the total margin balance. Traders are way more levered up now than they were in late 2007. This time, when the margin fairy comes to collect her teeth from traders who got smashed in the face, she’s going to be ruthless, as if a 99% loss wasn’t.

Just to give you an idea of where we are now, consider the FINRA margin statistics. At market top in late 2007, total NYSE margin debt (on which LVS trades) was $379.6 billion, combining both FINRA and NYSE statistics. By February 2009, margin debt had fallen below $200 billion as margin calls forced the liquidation of debt. More importantly though, when margin debt was at its peak in 2007, total credit balances remaining were $426.7 billion, still much higher than the total margin peak. As of June, we are now at $646.9 billion in total NYSE margin debt, with a free credit balance of $179.4 billion, much lower than the total margin balance. Traders are way more levered up now than they were in late 2007. This time, when the margin fairy comes to collect her teeth from traders who got smashed in the face, she’s going to be ruthless, as if a 99% loss wasn’t.

That doesn’t mean the carnage will once again focus on LVS, but it might. NYSE trading accounts are stuffed with 70% more debt than they were back then, with 58% less available credit. Those currently levered up won’t be happy if forced to sell. We are going to have ample warning before the next financial crisis, which will be preceded by obviously strong price inflation, a negative yield spread, and slowing money supply growth. When we start seeing those signs and margin debt starts to shrink, that will be the time to start scaling in to LVS on severe down days.

Right now, LVS is in a better situation in terms of revenue balance than it was before the Macau crash of 2014. Back then, VIP rolling chip revenues accounted for 56% of its total top line, multiplying rolling chip volume by win rate across all venues. Now, VIP makes up slightly less than 25% of total revenues. So we have a much more stable business model now, plus a good dividend which did not exist in 2007.

Just to give you another angle on the insanity of the 2008 LVS catastrophe, the LVS annual dividend per share is $3.00. The March 2009 low was $1.03. At that price, which would “only” require a 98.5% collapse instead of 99% from today’s prices, today’s dividend would translate into a nearly 300% yield. That means put in $50,000 at that price and you’ll have an annual 6-figure salary of about $150,000, not even counting capital gains.

Granted, during a crisis, Sheldon Adelson might lower the dividend during a financial crisis. Let’s say he cuts it by 66%, to $1 a year. That’s still a 100% dividend. That’s how crazy these numbers are. Even if the dividend is completely suspended, if you had buy shares at or near the low you’d still be getting plenty of income as the crisis passes and dividends are restarted. Judging by the 2014 Macau crash, a suspension of dividends is unlikely, considering that dividends were raised twice from 2014 peak to 2016 bottom, even though Macau was panicking at the time.

LVS debt is low, only 20% of market cap, and very manageable. The only major weak point recently has been the Marina Bay Sands rolling chip VIP segment, which was down 32.6% by volume. The company does not seem too worried about that, and kind of just blew it off in its recent conference call, just saying that “we have to get better”. Well OK, nothing’s perfect. Earnings from every Macau venue went up, and even room revenues, occupancy rate, and revenue per available room all went up in Singapore, so whatever is happening there is a VIP-specific problem.

VIP revenues though should really be treated as a bonus beyond a certain low baseline. Here’s a paragraph from the LVS November 2007 earnings call that shows why:

And finally, our VIP volumes have significantly exceeded our expectations and our non-rolling table game drop is steadily increasing, just as it did at the Sands in the early days. It was up over 32% in October when compared to September. So the transformation of the market is coming on strong and The Venetian Macao is paving the way. And as dramatic that this transformation is, we are clearly just at the top of the first inning, we are quite literally just getting started.

From there, the stock fell about 99%. So there is really no reason to get overly excited about great VIP numbers, nor is there much of a reason to get overly despondent about collapsing VIP numbers, unless you’re levered up and margined out and you’re relying on them, but then you deserve what’s coming.

There isn’t much of a reason to buy LVS specifically now, though keeping in mind that it could collapse for reasons totally unrelated to its own business, putting in an initial tranche (not on margin) with the intent to weather any drawdown shouldn’t do too much damage. The worst part of the ongoing trade war is still ahead of us, the yield spread is closing in on zero, and for stocks August/September is typically a crazy time. But considering past action in LVS shares, another broad margin call event could give investors a rare opportunity to lock in extraordinary prices for a fundamentally sound company that can handle a lot of stress. When that time comes, I’ll be pounding the table.