It’s always exciting when a new company earns its first profit. It piles in the longs, generates a lot of fanfare and positive press, top executives gush with pride and positive forecasts, everyone focuses on the bottom line numbers and how much money was made, the stock gets more followers etc. Bloomberry Resorts is enjoying all that now. The stock is up 50% since February on the release of its impressive earnings of ₱1.46B this quarter (about $33.5M), and it looks like after sinking down over ₱30B in debt to get its Solaire project moving, it has finally hit its stride.

It’s always exciting when a new company earns its first profit. It piles in the longs, generates a lot of fanfare and positive press, top executives gush with pride and positive forecasts, everyone focuses on the bottom line numbers and how much money was made, the stock gets more followers etc. Bloomberry Resorts is enjoying all that now. The stock is up 50% since February on the release of its impressive earnings of ₱1.46B this quarter (about $33.5M), and it looks like after sinking down over ₱30B in debt to get its Solaire project moving, it has finally hit its stride.

After all is said and done though, the real question is, how long can it run?

With Bloomberry, there is the obvious positive of a young company building a resort, in this case Solaire, and achieving profitability in the space of only 14 months. Management clearly had a plan, stuck to it, and executed it well. But there are a few other considerations here that need to be out on the table before we can declare Bloomberry a clear cut victory.

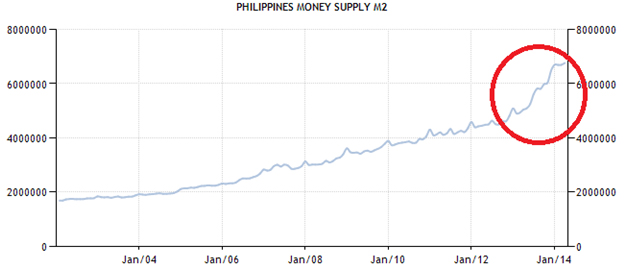

I mentioned last week in my review of Melco Crown that the situation in the Philippines, monetarily speaking, is far from stable. Here’s the graph again, with a big red circle around the unstable part.

Since the beginning of 2013, the Philippine Peso supply has skyrocketed. The effect of this is to enhance GDP and make it look like the economy is growing. GDP measures consumer spending, business investment, trade surplus (deficit) and the universal “fudge factor” of government spending. I say fudge factor because government spending doesn’t add anything. It simply redirects investment. When a central bank prints money, the government gets to spend it first and “add to GDP”. The fact that the Philippines’ GDP growth rate has not increased (currently at 1.5%) as a result of this huge growth in its money supply should be signaling alarm bells all over.

While I have derided GDP as a useful economic calculation in the past, it does say something. If the government is the first to spend the new money, and it usually is since central banks generally print money by buying government bonds, then what is happening in Manila being that GDP growth is stagnant must be excessive government spending and shrinking private investment. And since government has no way of knowing where the most productive places to spend money are absent the profit motive, it means there are massive malinestments occurring right now in the Filipino economy.

That’s just the picture in the Philippines. Where Bloomberry enters the picture is a little more complicated. The main source of its impressive revenue growth has been from its 47 contracted foreign junket operators, ferrying in super-rich Chinese on velvety blankets of supersaturated swank. While this major foreign revenue source insulates it from monetary problems from within Manila to some degree, Bloomberry admits its reliance on the VIP segment and says as much in its 10Q. Namely that profitability was achieved because of the higher turnover of VIP players. In fact, Bloomberry president Thomas Arasi noted in a recent interview with Bloomberg that revenues from junket-ferried VIP clients rose from “substantially less than half of gambling revenue last year…to close to parity with mass-market gaming.”

While there is nothing inherently wrong with junket operators, what is unnerving about them is that it is hard to know where the money is coming from ultimately. Not in the sense of illegal activity per se, but in the sense that, with the super rich, one never knows if the source of their wealth is market-based or political, or in other words relatively stable or fleeting. I’d say it’s a safe assumption that most of the targets of junket operators are bankers of one form or another or else closely connected to them, whose fortunes depend on the whim of the printing appetites of Central Banks. Their fortunes could go south very quickly when the printing stops, and with it the VIP clients.

It is beyond the scope of plausibility to dig in to the nature of every VIP client at Solaire and make a rational decision about the stability of such a revenue source. But my feeling is that it is a generally unreliable one and to build a business model based on it is dangerous. The problem is not at all limited to Bloomberry. 70% of Macau’s revenues, all casinos included, are estimated to come from junket operators bagging VIP’s. This is just another big reason I am not a big fan of Macau stocks right now, and one reason to be careful of Bloomberry.

Junket operators have also been known to conveniently disappear when they owe lots of money, which just happened earlier this month with one who owed $1.3B in Macau. The grey-to-black nature of the market these sharks prowl lends to this sort of thing.

Beyond the questionable reliability of continued long term VIP revenues, as with all gaming companies, I go straight to debt load and financing of that debt to see what’s up. In that sense, Bloomberry looks a little like the US Federal Government going into debt to raise GDP, not to the same extent of course, but Bloomberry went deep into debt, over ₱30B currently, to score that first ₱1.46B. Debt to equity is now 216% (page 55), which brings me to my next concern, and that is accounting practices and disclosures.

Public filings are vague when it comes to the company’s exact financial condition. It is unclear exactly how much of Bloomberry’s ₱30B debt it racked up getting Solaire off the ground is floating or fixed, and the company has up until now capitalized interest rate changes on debt in “Project Development Costs.” Those “Development Costs” or however the company terms them will go up as interest rates rise. Nowhere in its 10Q does the term GAAP (Generally Accepted Accounting Principles) show up.

No, I am not accusing Bloomberry of any impropriety or wrongdoing here. I am simply saying that judging by publicly available information, it is difficult to gauge the situation.

But back to the positives. Much like Melco Crown, Bloomberry is doing well given where we currently are in the business cycle. In the current monetary environment of low interest rates and flowing (probably banker related) VIP clients, Bloomberry can and will thrive. But the situation longer term is like a treadmill. Bloomberry doesn’t know it yet, but it is in a race against time. If it can grow fast enough to bring its debt down significantly before interest rates start to rise, it may reach escape velocity and survive the down phase of the business cycle.

All this considered, excitement over Bloomberry will likely continue in the short term as long as revenues and profit keep growing. Longer term, watch what the company does with those profits. If it pays down debt aggressively, then it is acting smart and a longer term hold is possible. If, however, it uses its newfound success to expand aggressively and double down on its debt burden, it would be time to get out.