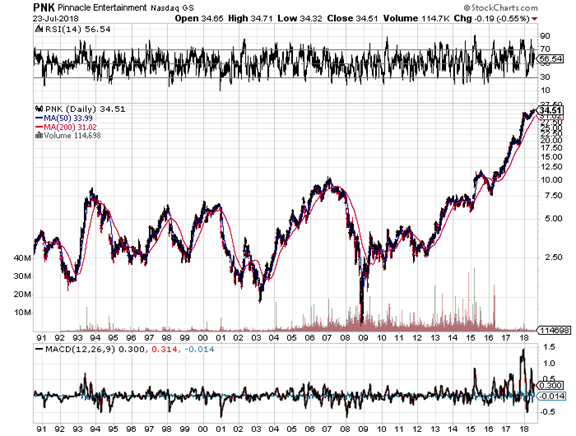

Rarely do fundamental trading patterns change for a stock, assuming the company remains basically the same. What has been, will continue to be, barring a fundamental change of the company itself. For regional gaming companies in the US, nothing has fundamentally changed since the 1990s. Sure, the companies have grown and done well, but they remain the same sort of momentum stocks that rally hard with the business cycle boom and fall hard with the bust. Looking at a long term chart of Pinnacle for example, the stock has never rallied on a slow-burn, neither has it gently declined over long periods of time. Either it’s zooming up, or it’s collapsing. If you own it, expect more of that.

A long term chart of any of the US regional gaming stocks looks both enviable and scary. Anyone who bought at market bottom in early 2009 now stands on gains of thousands of percent at least. 1000% for Pinnacle, 3,700% for Penn National Gaming, and 1,300% for Boyd. It can be tempting to try to establish a position now and try to eke out some of those gains, but it makes sense to first try to see why these stocks rally and why they collapse so hard. Is it for any fundamental reason, like earnings are revenues or growth prospects, or is it mostly just the nature of the way the regional sector trades? It looks like traders just tend to pile into these momentum plays all at the same time because that’s what everyone else does, and then exit at the same time when overall economic conditions worsen.

It’s easy to make a glib statement like, “These stocks are rocketing higher because these companies are doing awesome!” Maybe they are, but it pays to take a little time to see if they’re moving they way they strictly because of that, based on past movements. Granted, even if fundamentals weren’t the primary factor back then doesn’t mean it isn’t the case now, but chances are a stock will keep behaving just like it has in the past. So let’s take a look at how each of these companies was doing financially last time each of them exploded higher, and what was happening the last time they collapsed.

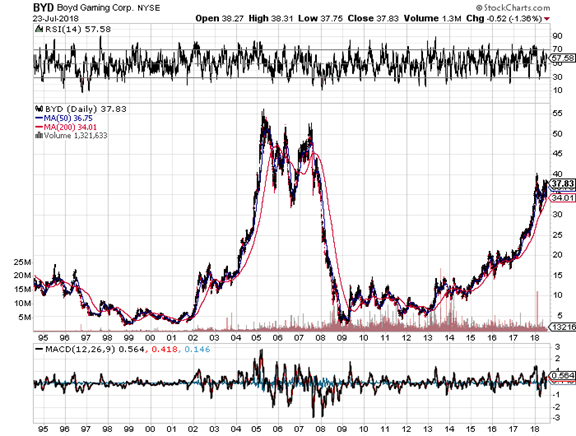

Boyd

From the beginning of 2004 to the beginning of 2005, Boyd moved from about $21 a share to $54. What justified that? Both revenues and earnings were up strongly from 2003 to 2004, so there was fundamental reason for some sort of rise. Earnings were up 172% and revenues were up 38%. Much of the bump was due to Coast Casinos merging with Boyd in 2004 and adding $380M to its top line, but revenues were up across the board. Then why did it fall so hard?

From the middle of 2007 to the middle of 2008 Boyd shares got destroyed. Interestingly though, revenue in 2008 was still 4.3% higher than 2004, while in 2008 the stock fell below 2003 levels prior to the parabola upward. Sure, income had plummeted, but that’s what happens when companies overextend themselves on additional debt assuming economic growth forever. Essentially, the rise up assumed consistent growth projected out decades based on the continued health of the greater US economy. That didn’t last, and the fall was even sharper than the spectacular rise higher.

But just like the rise up, Boyd fell too far to the downside and the collapse wasn’t justified either fundamentally. So eventually it exploded back up. Even now, both revenues and earnings have surpassed 2006 when the stock was over $50, and we’re now still below $38. That could be interpreted as more possible upside, or as serious overvaluation at the peak of the last boom. It’s a dangerous guessing game.

But just like the rise up, Boyd fell too far to the downside and the collapse wasn’t justified either fundamentally. So eventually it exploded back up. Even now, both revenues and earnings have surpassed 2006 when the stock was over $50, and we’re now still below $38. That could be interpreted as more possible upside, or as serious overvaluation at the peak of the last boom. It’s a dangerous guessing game.

Expect something similar to happen with the next business cycle, too. The current parabola in Boyd began in 2014 at around $10 a share. The usefulness in stocks like Boyd is just what they are – momentum stocks, both up and down, so it should go down further than fundamentals would warrant on the next trip south. If Boyd reaches anything near $10 again and its balance sheet is in condition to be strengthened at that point, then it will be a buy.

Penn and Eldorado

With Penn, 2008 revenues were only 0.5% lower than what they were at the stock’s peak in 2007. Excluding a $480M goodwill impairment, the company was still healthily profitable. Yet the stock fell below 2004 levels when revenues were less than half of what they were in 2008.

We can see the same thing happening with Eldorado Resorts. Capital gains have way outpaced fundamentals. Revenue has doubled since 2015, and the stock has increased by 1,000%, but net income has dropped by 35%. Bulls can hang their hats on Eldorado’s efforts to grow, which requires spending a lot of money of course and eating into earnings for the sake of the future. But come the next bust, the same thing that happened to Boyd and Penn in the past, will probably happen to Eldorado, too. There is nothing all that different between these companies and the types of investors they attract to say that the same thing won’t happen again.

Eldorado was a good momentum play, but it’s impossible to tell how far momentum stocks will go precisely because fundamentals don’t matter as much for determining valuation. It just has to do with people chasing a move and fearing missing out.

On the way back down, Eldorado should be a great pick, perhaps even the best of the momentum gaming stocks in the US. It will go down farther than it should in the next downturn, perhaps even to below $10 or so, if it follows the patterns of its cousins. Then it’ll be low risk and a good ride back up.