The case of GVC can get you to question the meaning of the term “public company”. On the one hand, GVC trades on a public exchange. A secondary AIM UK exchange analogous to the OTC in the United States, but you can own shares of it, so in that sense it’s public. On the other hand, very little pertinent information about GVC’s operations is actually publicly available. Annual and interim reports paste together the end result of all its operations but don’t tell you where any of it is coming from. In that sense GVC is not a public company. If you choose to own it, you’re not going to know exactly what you own unless you’re on the inside.

All we really know is that GVC makes money hand over fist and it hands over most of that cash to shareholders. GVC’s dividend yield is in the stratosphere, over 13% at current prices. It pays out almost like a real estate investment trust rather than a company focused on growth. Last year GVC made £41M and at a dividend of 55 pence a share, will pay out nearly £34M of that in dividends in 2015. That means over 80% of its income goes to shareholders. REITS pay 90% by law, so we’re pretty close here. That’s great if you’re looking for fast income, but it’s also a bit of a sugar rush. If GVC were a solid growth-focused company, it would keep some of that cash to invest in organic expansion.

All we really know is that GVC makes money hand over fist and it hands over most of that cash to shareholders. GVC’s dividend yield is in the stratosphere, over 13% at current prices. It pays out almost like a real estate investment trust rather than a company focused on growth. Last year GVC made £41M and at a dividend of 55 pence a share, will pay out nearly £34M of that in dividends in 2015. That means over 80% of its income goes to shareholders. REITS pay 90% by law, so we’re pretty close here. That’s great if you’re looking for fast income, but it’s also a bit of a sugar rush. If GVC were a solid growth-focused company, it would keep some of that cash to invest in organic expansion.

There’s plenty more to say about the unknowns here, but we’ll put the positives first. The good news, besides the obvious growth in top and bottom line, is that GVC is looking to move into the Romanian market, which is great because it means we actually know something about where its future business will be. A second big positive is that it is not as heavily reliant on sportsbook as it once was. In 2014, sports NGR and gaming NGR were pretty much equal. This compares to 2012 when sports to gaming was 76% to 18%, so the company is balancing its business well, or at least better than it was in the recent past. Third, its Greek market is recovering, though once again we just don’t know how crucial the Greek market is for GVC. All we know is that it is “important for the Group.”

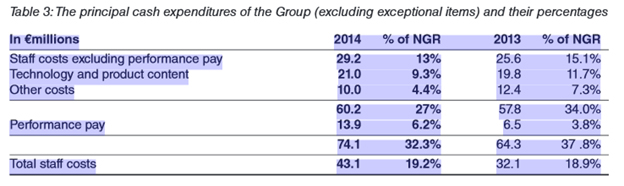

A fourth good sign is that expenses continue to drop in relation to its net revenue. Total staff costs plus performance pay is down to 32.3% of revenue from 37.8% in 2013, meaning the company is getting more efficient. Here is the full breakdown from the annual report.

A fifth good sign is that prior to the Bwin.party deal, GVC had almost no debt. That’s mostly irrelevant though since the merger, as they are now leveraged at 114% debt to equity. That’s not unmanageable, but it’s going to be hard to pay that off considering GVC hands over most of its earnings to shareholders. With a combination of debt service and let’s call the high dividends equity service, there will be almost no cash for investing in its own businesses. For a company like GVC that doesn’t have much competition, that’s OK for now, but it gives it little to fall back on in the event something changes. The term “competition” is barely even mentioned in its report, and only in a very general way in the sense that competition risk as a concept is a real thing (thanks for telling us) and that they are “constantly monitoring the competitive landscape”. But then no mention is made about what that landscape even is in the first place.

The public GVC reports read almost like marketing pieces. CEO Ken Alexander’s report to shareholders was a little too upbeat and very generalized. In his words:

I end my report on a very upbeat note – the Board believe (sic) the group has never been in a stronger position than now; robust trading; diversified products and markets; highly motivated staff; and technological developments which will allow the group to prosper. For this reason I am delighted to be able to announce a further increase in the quarterly dividend to 14.0 €cents per share plus a final special dividend of 1.5€ cents per share.

Sounds wonderful for sure, but where’s the substance?

It gets even more confusing when you compare current reports to past reports on Sportingbet. The most recent report for Sportingbet that I could find from before GVC acquired it is from October 2012. There it says that most of Sportingbet’s revenues, in fact more than 80% of them, come from regulated markets. See page 16. But then why hide the breakdown now? A pie chart there also shows Australia as the biggest revenue generator for Sportingbet, but Australia is not even mentioned at all in GVC’s latest annual report. Neither are any of the countries substantively mentioned where Sportingbet has a presence.

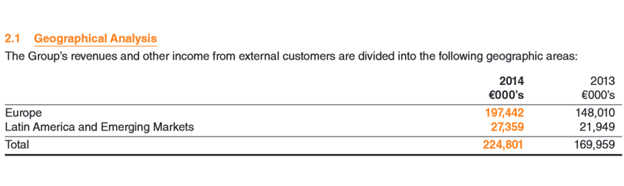

All we know of the geographic breakdown is this. It doesn’t tell us much:

All of this is quite strange, and it seems like GVC pays its shareholders so much in an attempt to fend off too many annoying questions. Just to be clear, I am not accusing anyone of any wrongdoing. It makes sense to keep the picture vague if you can get away with it so as not to give away hints to potential competitors. The only thing is that it means GVC is being very protective of its markets and disclosing the least amount of information possible, and that should make shareholders just a bit uneasy. It means there are weak spots that the company does not want anyone to know about.

All of this is quite strange, and it seems like GVC pays its shareholders so much in an attempt to fend off too many annoying questions. Just to be clear, I am not accusing anyone of any wrongdoing. It makes sense to keep the picture vague if you can get away with it so as not to give away hints to potential competitors. The only thing is that it means GVC is being very protective of its markets and disclosing the least amount of information possible, and that should make shareholders just a bit uneasy. It means there are weak spots that the company does not want anyone to know about.

The best long term strategy for GVC if they’re not going to invest in organic growth is preemptive defense against any regulatory snafus. In order to maintain its impressive margins, GVC needs to try to build any regulatory regime that may emerge as a shell around itself. This is not easy to accomplish and requires a lot of lobbying. It’s what Big Pharma and Big Tobacco basically do, and it’s not very tasteful but you can’t blame them.

For now, GVC will continue to be a high-yield high-risk play where you don’t even know what you’re buying when you buy it. Sure, the growth is there, but you don’t know where it’s coming from or when competition will become a factor. This probably has a lot to do with the shares being listed on the AIM secondary exchange instead of the main London exchange. A primary listing would probably mean more disclosure which GVC doesn’t want to do.